NYCB Vol. 15 No. 8 - Glass Pieces

- Lauryn Johnson

- May 7, 2025

- 4 min read

Updated: Jun 28, 2025

Arlene Croce: "In his latest work for New York City Ballet, Jerome Robbins uses a Glass score; he even uses a modicum of the minimalism associated with Glass choreographers such as Childs and DeGroat.

"The stage is hung with a plain beige sheet, lined like graph paper; most of the dancers wear practice dress and jazz shoes. It all has the look of some new, pristine adventure, yet what Jerome Robbins comes up with is a Jerome Robbins ballet.

Exactly what the music ordered.

Glass Pieces is in three parts. The first two are built on selections from the CBS record Glassworks; the third uses the opening instrumental section of the opera Akhnaten, as yet unrecorded. As a Glass sampler, the pieces are well chosen. They give us hard- and soft-core Glass. But they also give us his strengths and weaknesses. 'Rubric,' laying down deep chords of steam-whistle-like sound over a burbling, pulsating accompaniment, is followed both on the record and in the ballet by "Façades," a smooth and serene intertwining of two melodies, one wavering, one steady. 'Rubric' and "Façades" are the most seductive tracks on Glassworks, and for Robbins they work together as classic audience psychology---stir 'em up, quiet 'em down. "Rubric" has radical heat and energy, while

"Façades" lingers on the borderline of convention. The pounding drums of the Akhnaten excerpt, to my ear, cross that borderline and end deep in jungle-movie-soundtrack territory. And the extended finale that Robbins has devised to that music is the weak part of the ballet. He doesn't give in to the convention-he can't, because of the peculiarly restraining rhythm-yet he's uncomfortable with the alternative, which is to pretend that Glass is being as pure as he is in 'Rubric.'

"Like the rhythm of rock, Glassian rhythm is static; as movement, it takes you everywhere and nowhere. Its sensibility is Eastern; its mode is ritualistic. To a Western romantic like Robbins, rhythm is abstract or anecdotal. He succeeds in making anecdotes of 'Rubric' and 'Façades': he tells us the story of the music.

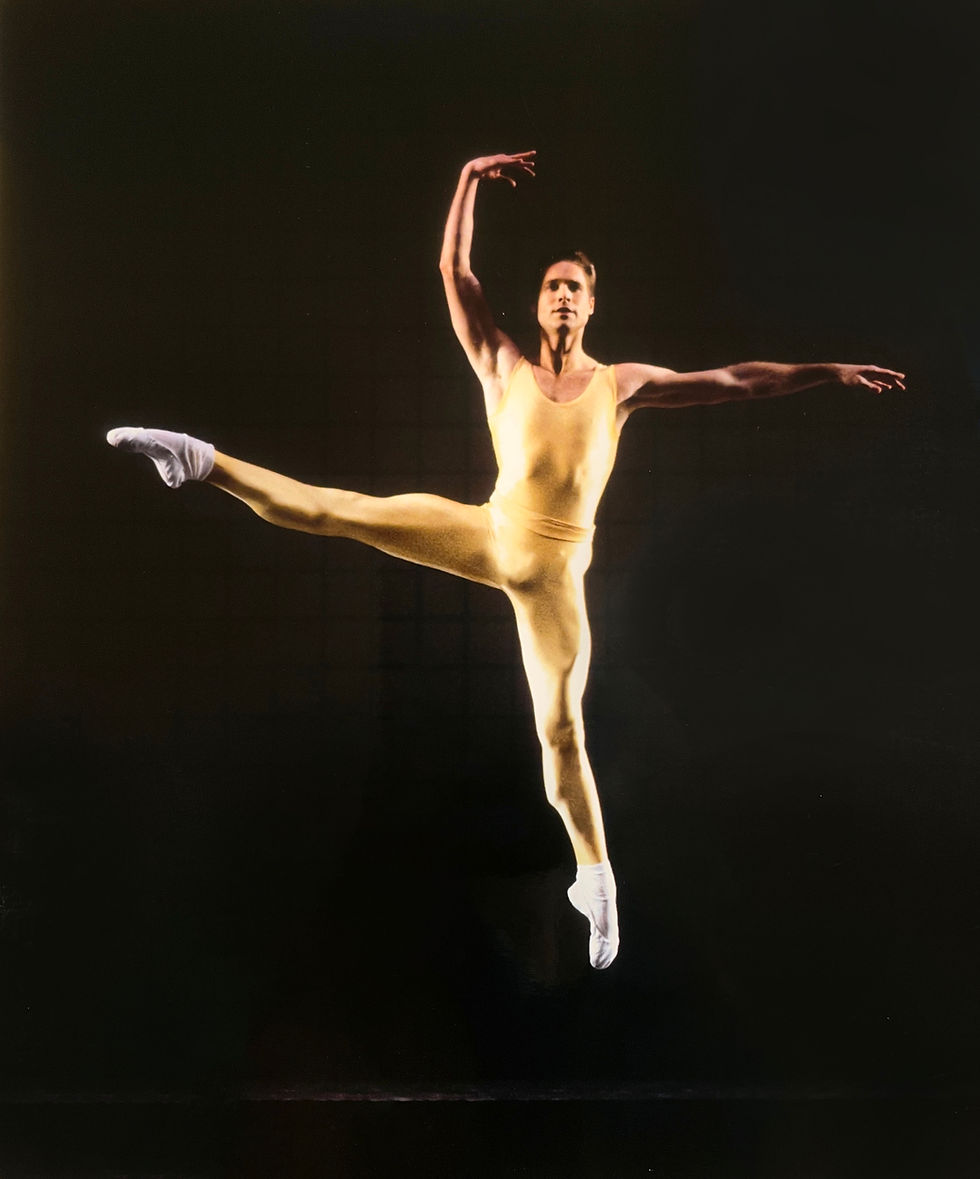

"Rubric" opens pell-mell with a nondescript horde of dancers walking--barreling around the stage in various directions. Into this rush-hour mêlée drop two ballet dancers (assemblé descent), to be lost in the swarm, then recovered in time for a brief pas de deux in conventional ballet syntax. The horde returns, and two more aliens arrive, clad like the other two in Milliskin tights and toe shoes. The four of them are together in a double duet, then the horde fills the stage again.

"The filling and emptying of the stage, the arrival of the aliens (three pairs in all), their disappearances and reappearances all this fits perfectly with the alternating strands in the music. The trafic pattern occurs four times, with slight variations each time; by the last repeat we see quite clearly that the process could go on forever, at which point everything stops and the scene blacks out.

"Choreographers of Glass's generation (he was born in 1937) don't try to explain the peculiarities of his music-they just accept them. Older choreographers may see the music's strangeness as a subject in itself. For Robbins, the fact that the music is sunk in a ritualistic mode means that a story can be constructed about it a story that seems to tell us something of the impervious, aimless rushing about we do in our lives, never stopping to notice the wonders in our midst. In 'Façades,' the ritual is again double-stranded. One melody oscillates like the path of a moonbeam on the surface of a lake, and the other melody spans it in slowly shifting single-note progressions carried by the high winds. Robbins translates the slow melody into a floating, rather mindlessly beautiful pas de deux for Maria Calegari and Bart Cook, while the all but motionless oscillation becomes a line of shadowy figures inching along in profile at the back of the stage: the piddling continuity, as it were, of daily life. Robbins doesn't ever mix the two motivic stands (though Glass does); his pas de deux could have been done for any other ballet. But then his point is that the wonderful events in life are different in kind from the ordinary events. They may interpenetrate, as in "Rubric," but custom prevents us from seeing this. In "Façades," beauty is enclosed in an entirely secret realm. Calegari and Cook at one point run to the line of figures and break through it it goes on as if they'd never touched it. Yet it's the humdrum background, not the ravishing foreground, that one wants to watch. Robbins's minimalistic choreography includes about a dozen steps, all as tiny as the inchworm shuffle that gradually carries the line off, and the way the minutiae accumulate, with a sidestep or a kneel or a pause added for every repetition of the sequence, makes a hypnotic spectacle. In Akhnaten, Robbins's motifs spread beyond the two parallel strands he's worked with up to now, and he again fills the stage, this time with prancing contingents of boys and girls. You can feel him trying to break out into abstract rhythm. All that happens is a series of devices for modulating and containing the force of Glass's rhythm; Robbins never does succeed in inflecting it."

--Arlene Croce

Comments