ABT 85 - Fokine's Les Sylphides

- Lauryn Johnson

- Oct 18, 2025

- 9 min read

From Diaghilev and the Ballet Russe by Boris Kochno:

A romantic reverie in one act by Michel Fokine. Music by Frédéric Chopin, seven piano pieces orchestrated for the Ballets Russes production by Sergei Taneyev, Anatole Liadov, Alexander Glazounov, Nicholas. Tcher-epnine, and Igor Stravinsky. Choreography by Michel Fokine. Décor and costumes by Alexandre Benois. (In 1917, a new set by Carlo Sokrate replaced the Benois décor.) First performance by the Ballets Russes: Théâtre du Châtelet, Paris, June 2, 1909. Principal dancers: Anna Pavlova, Tamara Karsavina, Alexandra Baldina, Vaslav Nijinsky.

The first version of this ballet, entitled Chopiniana, was created for a benefit performance at the Maryinsky Theatre, in St. Peters-burg, on February 10, 1907. For this production, the orchestration was by Glazounov. The mise-en-scène was borrowed from the Maryinsky's stock: white tutus "à la Taglioni," and a section of the backdrop for the third scene of Sleeping Beauty, painted in 18go by the stage designer M. I. Botcharov. However, for "The Waltz," new costumes were made after sketches by Léon Bakst.

The same version, retitled Dances to Music by Chopin, was presented at a benefit performance at the Maryinsky on March 8, 1908.

A new version, entitled Grand Pas to Music by Chopin and orchestrated by Glazounov and Maurice Keller, was offered at the graduation exercises of the Imperial Ballet School of St. Petersburg, held at the Maryinsky on February 19, 1909.

The following is Michel Fokine's account of the creation of his ballet, Les Sylphides from his autobiography, Fokine: Memoirs of a Ballet Master:

The cast was glorious: Anna Pavlova, Olga Preobrajenska, Tamara Karsavina, and Vaslav Nijinsky. Pavlova flew across the entire stage during the Mazurka. If one measured this flight in terms of inches, it actually would not be particularly high; many other dancers jump higher. But Pavlova's position in mid-air, her slim body — in short, her talent — consisted in her ability to create the impression not of jumping but of flying through the air. Pavlova had mastered the difference between jumping and soaring, which is something that cannot be taught.

Karsavina performed in the Waltz scene. I feel that the dancing in "Les Sylphides" was especially suited to her talent. She did not possess either the slimness or the lightness of Pavlova, but in "Les Sylphides" she demonstrated that rare romanticism which I seldom was able to evoke from other performers.

Preobrajenska performed the Prelude. In this I made use of her exceptional sense of balance. She would just freeze on the toes of one foot, and in a dance almost without jumps was able to project the feeling of ethereality. One of the shortcomings of this wonderful dancer was her inclination to improvise. After dancing the Prelude exactly as I had created it, she repeated it for an encore entirely differently. She had very often done this in the old ballets, but in "Les Sylphides" I felt it was out of place. There were so many dances in that ballet that, if everyone repeated his number, there would be no concept left of the ballet as a unit.

I should like to emphasize the inadmissibility of improvisation in my ballets. To me a ballet is a complete creation and not a series of numbers, and each part is connected with the others. This is not a theory;

I feel that way, for it is my approach to creation.

I did not plan to have a different ending for each dance. It just so happened that in the Mazurka Pavlova ran off the stage; in the Waltz duet she left with a pas de bourrée on toes; Karsavina terminated her number with a final pirouette and stopped on toes with her back to the audience; Nijinsky, after his jump, fell on one knee, with his hand extended as if to a vision; Preobrajenska froze on toes facing the audience as if imploring the orchestra to play still more softly.

All these were different endings. In her improvisation, Preobrajenska left the stage on toes, in the same manner as Pavlova was to do immediately after. Of course her improvisation did not help Pavlova, or the ballet as a whole.

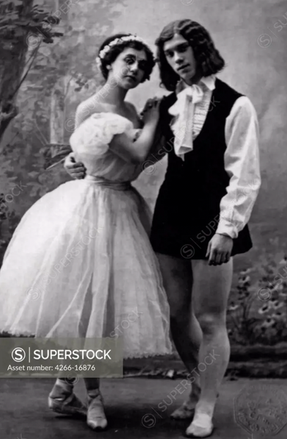

Nijinksy and Karsavina in Les Sylphides

I believe that his role in "Les Sylphides" was one of Nijinsky's best roles. This ballet contains no plot whatsoever. It was the first abstract ballet. But still I would describe Nijinsky's participation in it as a role and not a part, because it did not consist merely of a series of steps. He was not a "jumper" in it, but the personification of a poetic vision. The role calls for a youth, a dreamer, attracted to the better things in life. It is absolutely impossible to describe the meaning of this impersonation and of this ballet. On numerous occasions I have had the opportunity to write the synopsis of "Les Sylphides." I have known many critics who had a greater mastery of words, and who described it better than I did. I have read many descriptions of this ballet in programs compiled by experts — and yet I have never been able to find a satisfactory verbal elucidation of this ballet.

When I call attention to the "improvements" added to this ballet during the last thirty years, I realize that many dancers and ballet masters have not understood it either. Yet it seems too easy. Of course at times the dance is capable of expressing clearly that which is not expressible in words. But to understand, to grasp the hidden meaning of the dance — for this, one requires a special spiritual quality.

I know that there are cultured people who know the history of art and who are familiar with what the greatest minds have said on this subject, who are capable of inundating the listener with quotations — but it is plain to me that the dance has passed them by. They have not assimilated, they fail to understand the movements or gestures.

It was just the opposite with Nijinsky. I definitely know that, when I began to work with Nijinsky, he had read nothing about art, nor had he given the matter any thought. When he was a student, he would stand and watch me exercise in the rehearsal hall for a long time. While resting between exercises and combinations, I carried on a conversation with him. I knew he was a very talented boy, for at the time I was a beginning teacher and a young dancer, and was greatly disturbed that the school gave no instruction on the history and theory of art. When I talked to Nijinsky I asked him whether he was interested in this problem and in reading. No, he was not interested, and he had not yet read anything about art. Even later I never heard him discuss this subject. He was not an articulate conversationalist, but who could so quickly and thoroughly understand what I tried to convey and explain about the dances? Who could catch each detail of the movement to interpret the style of the dance? He grasped quickly and exactly, and retained what he learned all the rest of his dancing career, never forgetting the slightest detail.

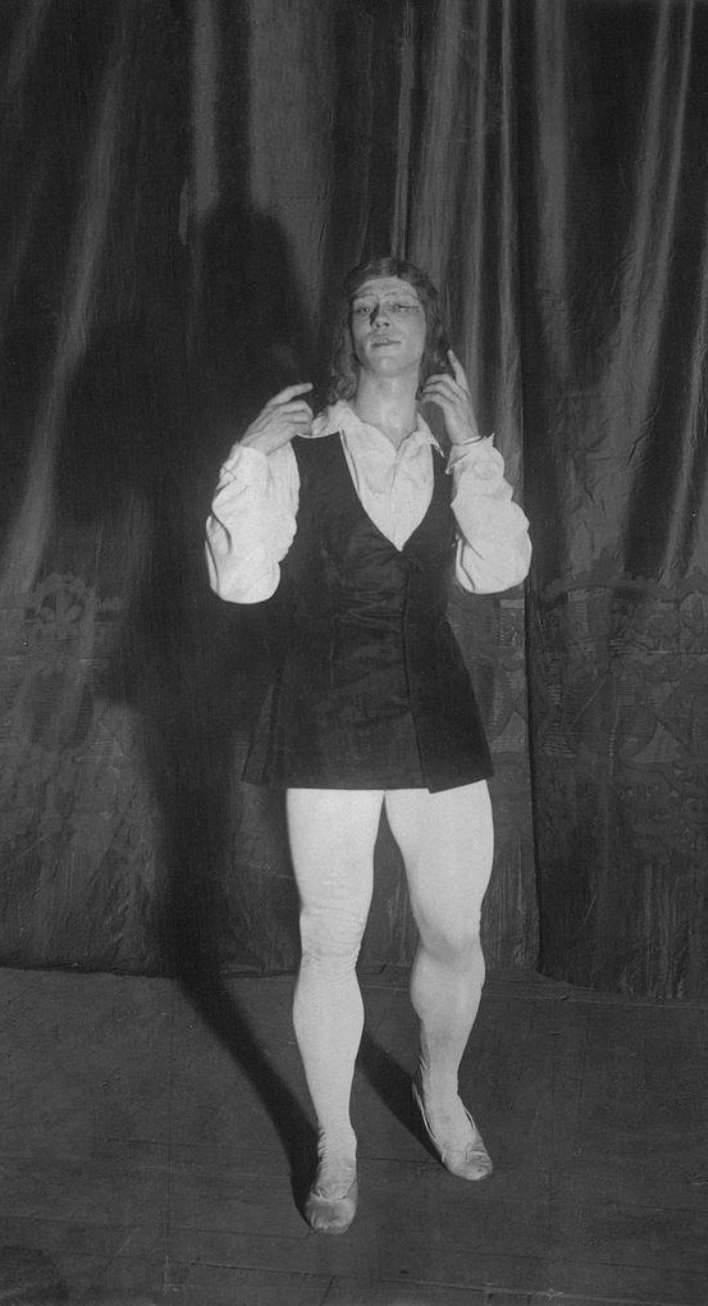

Nijinsky as the Poet in Fokine's Les Sylphides

The dancer partner (I am reluctant to use this term when describing the male role in "Les Sylphides") is represented by a youth, a poet, entirely different from the accepted male roles in the ballet of that time. It was previously essential that all male variations include double turns in the air and end with a preparation and a pirouette. But the most important difference between the new and old classic dance was in the expressiveness. Previously, the dancer emphasized in all his movements that he was dancing for the audience's pleasure, exhibiting himself as if saying, "Look how good I am." This was the substance of each variation in the old ballets. Even, at each new rehearsal of "Les Sylphides" I had to tell the dancer:

"Do not dance for the audience, do not exhibit yourself, do not admire yourself. On the contrary, you have to see, not yourself, but the elements surrounding you, the ethereal Sylphides. Look at them while dancing. Admire them, reach for them! These moments of longing and reaching toward some fantastic world are the very basic movements and expressions of this ballet."

My explanations were not always understood by the performers. Very often, after my persistent corrections, the dance was first performed as I wished it. But later on, the dancer would revert to the usual execution. Again self-admiration, self exhibition and an attempt to please the audience would reappear.

To Nijinsky I did not have to explain this new meaning of the dance. No speeches, no theories were necessary. In a few brief moments I demonstrated the Mazurka, danced it in front of him, made a few corrections, and resumed the composition of the other variations.

Nijinsky immediately — and forever — assimilated and understood all I wanted. One movement, however, became his favorite. When creating the image of the dreamer, I pictured him with long hair parted on the side and therefore, in movement, falling over one side. (Such hair styles were worn at the time of Chopin.) I introduced in this dance a movement suggesting the brushing away of a lock of hair from the face: one hand languidly reaches forward while the other performs the movement, accenting, as it were, the youth's desire to observe more clearly the apparitions around him. Nijinsky became very fond of this gesture. Without further explanation from me, he felt its genuineness for that specific moment. But — he not only never omitted this gesture in "Les Sylphides," he introduced it into other ballets, as for instance in the role of the Slave in "Le Pavillon d'Armide," where there was no long wig, but a turban, and the movement of brushing the hair to the side was uncalled for.

I created "Les Sylphides" in three days. This was a record for me. I have never changed anything in this ballet and, after thirty years, I still remember every one of the slightest movements in each position.

Some of the corps de ballet groups accompanying the dancing of the soloists were staged by me during the intermission, just before curtain time.

Ballet Russe Premiere of Les Syliphes in Paris

My faithful regisseur, Sergei Leonidovich Grigoriev (at the time called "Egorushka"), who looked after the administrative chores of all my charity performances, said:

"We really have to start. The intermission has been too long."

"Just a minute, one minute, I have one more group," I replied, placing the dancers on the floor and humming the melody of that part of the music where the dancers were supposed to change the position of the arms.

"Did you hear me? Did everyone understand?"

The first group was ready.

"Begin!"

That which was so hastily conceived was never changed by me.

Many times haste was not only not a hindrance but, on the contrary, I created better when I did not have too much time for meditating on alternatives. I created as I felt. Art originates not from pondering but from feeling.

The "Second Chopiniana" made its debut in Russia, and later, renamed "Les Sylphides," was presented, without any changes or alterations in choreography, in Western Europe. Since then it has become the "required" ballet of every major company in the world.

La Pavlova and Nijinsky was painted following the performance of Les Sylphides by the Ballets Russes on June 2, 1909. Sergei Diaguilev's dance company created a sensation throughout Parisian society, which fell under the spell of the young Russian prodigy, Vaslav Nijinsky. He is accompanied by the prima ballerina Anna Pavlova and the corps de ballet faintly visible in the background.

In this masterly composition, the famous couple appears in the spotlight in the foreground. Nijinsky, "like a black and white butterfly near the sylphs," his long hair worn loose, seems to take flight with a wholly feminine grace. He was the first male dancer to rise "en pointe", a practice that had been reserved for ballerinas.

In a letter to his mother dated June 9, 1909, Flandrin shared his impressions: "The energy and good health of these dances are truly admirable and range from Siberian, Hungarian and Neapolitan dances, to the remarkable dances of Les Sylphides, all clad in the white costume of La Taglioni, dancing in the moonlight...". The ballet Les Sylphides was a pure dance performance, with no plot, no subject, but instead a romantic reverie set to the melodious music of Frédéric Chopin.

During these Ballets Russes performances, Flandrin sketched the dancers first hand, simplifying the shapes, more like suggestions than precise contours and figures. Thick and lumpy paint, applied in broad touches, pares volumes down to the essential. Spectral light brings out the sketched, suspended bodies, indicated only by a few brushstokes. The colour blue is used to blend the different planes together. A Marian blue, dear to Flandrin, bathes the étoile couple in a spiritual aura.

Comments