NYCB Vol. 17 No. 6 - Prodigal Son, Edward Villella

- Lauryn Johnson

- Jan 23

- 26 min read

The following text comes from Edward Villella's autobiography, Prodigal Son: Dancing for Balanchine in a World of Pain and Magic.

The major breakthrough in my career came in 1960. I was cast in Prodigal Son, and in typical New York City Ballet fashion no one ever talked to me about it officially. I wasn't even aware that Prodigal was being revived. I was standing around waiting for a rehearsal to finish when Diana Adams turned to me and said, "Oh, congratulations."

I said, "About what?"

"Don't you know?"

"Know what?"

"You're going to be cast for Prodigal Son."

In the 1959-1960 winter season, my third in the company, I think Balanchine felt that I was ready to accept a major challenge, to move on to the next step. I don't think he had much enthusiasm about the revival of Prodigal Son, or for that matter the ballet itself. The assignment to choreograph it had been imposed on him in 1929 by Diaghilev, who needed a Serge Lifar vehicle. Lifar was a leading Ballets Russes star. Balanchine didn't have much respect for Prokofiev, who had composed the score and who treated him as an upstart. Making the ballet had not been a joyous experience for anyone concerned. Nothing proceeded easily or on schedule, and in order to get the painter Georges Rouault to finish the sets and costumes in time for the premiere, Ballets Russes officials had to lock him in a hotel room, stand guard over him, bring him food. He was literally imprisoned until he finished his task. Sometimes it seemed to me as if Balanchine were reviving a dusty work he didn't care about just for my benefit. Maybe he was staging the ballet because he wanted to see it again, but I hoped that he was searching for a role with which to develop me. Even so, he didn't seem terribly interested in what we were doing.

The dramatic element in Prodigal Son was the major challenge for me. I had never seen a Balanchine work like this ballet, and I didn't really understand its tradition. The Prodigal is a demi-caractère role with nothing delicate about it. I was comfortable with that. I hadn't yet achieved classical proficiency. But the ballet tells a story, and I had to create a character. The style puzzled me. I had to figure out a way to perform the gestures without feeling self-conscious. Although it has a narrative (unusual for Balanchine's Work), Prodigal Son is still very much a Balanchine ballet. The plot is told economically, the choreography is tied to the music.

I tried to read as much as I could about the ballet. I had Balanchine's book Complete Stories of the Great Ballets, and I read the entry on Prodigal over and over. I even read the Bible. I examined the Rouault sets and costumes, I looked at photographs, and I listened to a recording of the score by Leon Barzin. The tempi were slower than the pianist played them at rehearsal, but at least I could listen to the music and get to know it. I wanted at least to absorb the atmosphere of the ballet. At home in Bayside I worked in front of a mirror, trying different expressions. Balanchine taught me the part, but typically he didn't spend much time doing it. He often relied on ballet mistresses to teach his choreography to the male dancers, and he worked more closely with the women. My feeling was that he wasn't really interested in working with anyone on this role.

I learned the opening and closing scenes in two twenty-minute sessions with Balanchine. He taught me the pas de deux in a half hour, and then I didn't see him again until the final rehearsal on the day of the performance. A former ballet mistress, Vida Brown, was coaxed out of retirement to stage the ballet because nobody in the company remembered it very well. Lifar had created the role, and Jerome Robbins, Hugh Laing, and Francisco Moncion had each performed the part with great distinction. But I didn't really have an example before me when I began to develop it.

Left to right: Serge Lifar, 1929; Jerome Robbins, 1950; Francisco Moncion, 1952; Hugh Laing

Balanchine had first staged the ballet for the company in 1950. Robbins and Tallchief had danced the leads. Moncion, who had most recently danced the role, was still a principal, but in typical NYCB fashion no one asked him to come to the rehearsals to help out. It must have been a painful thing, and I think he suffered terribly. No one said,

"Frank, this role is now being passed on to another dancer. We want you to under-stand." No one had that sensitivity. It was a Balanchinian, old-world, Russian way to deal with a difficult situation. I could see that Frank was hurt, but there was no way I could help. And Balanchine discouraged it. "No, you don't need Frank," he said. "Frank is big, big man. Big muscle man. You're boy."

Balanchine abhorred anything that might create confrontation, and everyone took the cue from him. We just swallowed hard and put up with what he dished out. We had to carry around our feelings of pain and rejection-and anger. We couldn't express them to his face.

Vida Brown's rehearsals, concerned mainly with reproducing the ballet and setting it on its feet, were useless for my purposes. Recreating a ballet section by section is painstaking work. Scenes or movements are often staged out of sequence. Eventually, usually at the last minute, it all comes together.

Most of my time in these rehearsals was spent working with the boys who played my drinking companions. Balanchine showed up on one occasion to look at what the boys were doing. As I watched what he showed them with his own body, how he related gesture to music, I began to sense the basics of the style.

Balanchine never spent a great deal of time talking about his choreography or telling us, for example, about the biblical story of the Prodigal, how he had researched the story for the scenario, or arrived at particular moments in the action. But his offhanded conversations contained key phrases. I had to be on the lookout for them and recognize them. They were gone fast. I sometimes felt he was not only testing our ability to understand but our commitment.

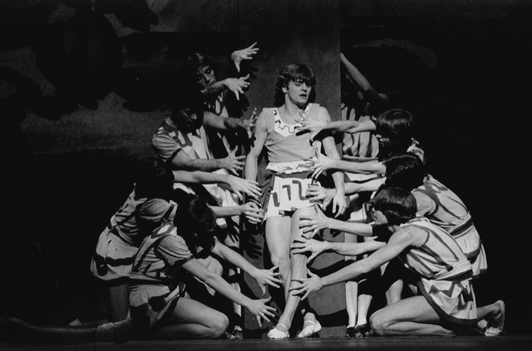

At one point during the rehearsal, he said to the boys, "You're protoplasm." The word suggested an image of primordial slime, and this was very helpful. Later, working on the section in which the drinking companions run their fingers up and down the Prodigal's exhausted, nearly naked body as if to strip it further of worldly goods, Balanchine said to them, "Like mice." It spoke volumes. It was as if they were going to eat my flesh, and it made me cringe.

At the dress rehearsal, Balanchine's comments were eye-opening. In the ballet's central pas de deux, a difficult moment occurs when the Siren sits on the Prodigal's neck, without holding on to anything for support. Balanchine said to the dancer, Diana Adams, "Well, it's like you're sitting and smoking a cigarette," and that remark recalled to me images of models in old cigarette advertisements. I could see the way she would be sitting, the way she'd pose, and the way I would have to balance her. It was an image of female dominance at the expense of male immaturity and intimidation.

At still another moment in the pas de deux, the Siren rests on the Prodigal's head as he sits with his knees raised. She puts her feet on his shins, just below his knees, and he holds her ankles. She then rises up from his head into a standing position as he lowers his knees to the floor. Now she's in an upright position, and she steps off the Prodigal's legs onto the stage. Balanchine said, "Good. You lower her like elevator." I was to feel like her servant, like the elevator operator, if you will.

These simple statements conjured up images of what Balanchine wanted the ballet to look like. He made more brief comments that helped me. At the start of the pas de deux the Siren and the Prodigal stand on opposite sides of the stage. They put their hands on their hips and lean toward each other. You really have to lean into hips and put hands like they're growing out there," Balanchine said. He was trying physically and mechanically to explain the gesture. Then he stopped, looked us in the eye, and said, "Icons. You know, dear. Byzantine icons." I said to myself, "Oh my God, icons." The image made me understand the movement and I looked at as many reproductions of Byzantine icons as I could.

Screenshot of Karin Von Aroldingen and Mikhail Baryshnikov and a Byzantine Icon

Diana Adams was also a help because she intimidated me personally, and I could inject this element of fear into my onstage relationship with the Siren. Diana was an experienced ballerina of great technical accomplishment and considerable distinction. She had a perfect neoclassical body, and Balanchine admired and respected her. By contrast, I was just a kid. On-stage, one look from her menacing, steely eyes would send a shudder through my body. She embodied the mythic qualities of Woman, Mother, Religious Goddess, Sexual Goddess. It was just a pretense, of course, but onstage it seemed real to me. And she towered over me. On pointe she was over six feet tall. Offstage, she wasn't easy for me to talk to. Her façade was impenetrable. Looking back, I would characterize her as high-strung. She was withdrawn and tense. Her glance shifted all the time, and her hands were always moving. She didn't easily bare her thoughts or reveal herself; she was someone with whom it was difficult to be intimate. Of course my state of mind made her seem that much more remote.

Diana Adams

During the technical rehearsal, I tried to get a sense of the lighting and what the set looked like. Sometimes dancers are sort of detached from these sorts of things. In performance, we're enclosed in the proscenium arch, inside the ballet. Because of the side lighting, the footlights, and the spotlights, we're often in a ring of light. We look out into this black tunnel, which is the audience. A dancer gets a different sense of a production when he looks at the set from the audience's point of view. I could see that the slashes of black on the backdrop corresponded to the slashes of black on the costumes and bore some relation to gestures and the bold colors of the music. It all began to come into a kind of focus I still couldn't articulate.

The early performances of Prodigal Son were quite successful and received good reviews. John Martin wrote in the New York Times that I danced the role like "a house on fire ...Prodigal Son dates back thirty years... but it may very well be that it has never been presented so beautifully as this. Edward Villella in the title role and Diana Adams as the Siren have evolved characterizations of extraordinary authority and richness of color, and they play together with an unbroken line of tension. It is a pleasure to see Mr. Villella the master of such a close stage relationship... He's high-tempered, callow, passionate .. what is notable is that he communicates this so convincingly in terms of his actual dancing, technical though it remains. His final return and repentance are profoundly moving."

Balanchine said little about the performance. He didn't rush backstage and congratulate me or anything like that. But he continued to cast me in it, and as time went by, every now and then he offered a few words of illumination about my performance.

This was the beginning of my relationship with the role that I was perhaps more closely associated with than any other. Prodigal Son was the first ballet that made me think and start to expose my real self. I continued to investigate this role until the day I stopped dancing, and in fact, the process of investigation continues today, when I stage it with my own company, the Miami City Ballet, or when dancers call and ask me to coach them in the role. I gladly give whatever advice I can. As I worked over and over on Prodigal Son, through every phase of my career, it occurred to me that no one had the same interest in this ballet as I did. People began to think it was created for me. In the second season of the revival, Balanchine himself said to me, "This is your ballet. I stage it this time. Next time you stage. I'm never going to stage it again."

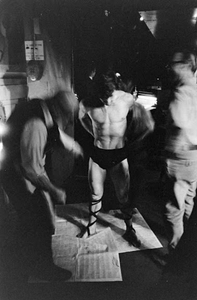

Warming up for Prodigal Son was special. The body makeup took a half hour to put on, and if I applied it before warming up, it rubbed off while I worked. Putting it on after warm-up meant that my muscles would cool, so I had to put it on before. (I once tried dancing the ballet without body makeup, but I felt unclean, and under the lights my skin had a sickly, washed-out glow.)

Before applying the makeup, I'd swallow a few muscle relaxants and then examine the chafed or worn-away skin on my knees and feet. Once the body makeup was on, I'd warm up in an empty studio. Then I'd get into my costume and go down to the stage, keeping warm in the wings by doing very gentle tendus in the minutes that remained until curtain. In most ballets I wore tights; in Prodigal I was bare-legged and barefoot in my slippers, and that took some getting used to.

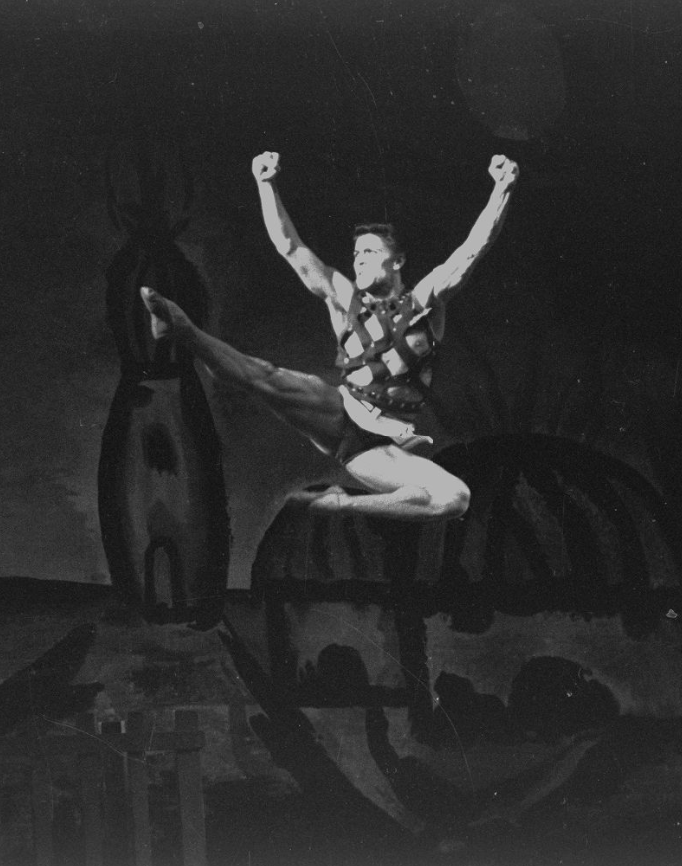

No matter how hard I tried to stay warm in the wings, however, my muscles soon cooled down because of the scanty costume I was wearing. But if I put on tights to keep myself warm, the makeup rubbed off on them. The solution I came up with was leg warmers, woolen leggings that cover the dancer from the thigh to the ankle. And I'd also wrap a towel around my neck and shoulders and put a robe on over that, work and not rub away too much makeup. By now the picket fence and the flat that depicted the tent, the basic scenery for Prodigal Son were in position onstage. I'd finish this mini-warm-up and then step out and try out the steps of the variation I sometimes felt that success of the opening movement— indeed the whole ballet-depended on this variation. It contained the jump that had become the signature pose of Prodigal Son. The variation is dramatically important to the narrative. I sauté high in the air with one leg out in front of me, the other tucked in under my torso, my arms up over my head in the air.

It's a leap of defiance, the gesture of someone desperately seeking freedom. It should come as a shock, a surprise. But at most performances it seemed as if the audience was anticipating the jump; even those people who'd never seen the ballet had heard about the step or seen a photo, and they were waiting for it. It was always absolutely necessary to be certain that the jump was firmly established in my muscles and bones so that it was like a conditioned reflex. Once the jump occurred, the audience would relax, sit back, and enjoy the rest of the ballet. I would feel better, too.

The Prodigal exits in the first scene by jumping over the fence downstage right, turning, and running off into the wings. I always practiced this jump, too. Billy Weslow would hold his hand higher and higher for each jump, and I'd try to reach the level of his palm. Going over the fence could present a problem. If I was tired, my left leg sometimes went limp. This was my turning and landing leg. I had previously injured it and it worked slower than the right one. A couple of times it came up so late on the jump that it grazed the top of the picket fence.

If the dancer who was playing the Siren was unsure about sitting on my head or my neck, as she had to do during the pas de deux, we would try out the movement. I'd ask the conductor to go over the opening variation for me. The tempo attacks the dancer. I wanted to attack it, so I'd set it with the conductor and go through the whole variation.

It was also important for me to check the stage, especially the areas where I had to move on a diagonal or cross from one end to the other. Because there are such abrupt movements in the ballet, I really had to have a very secure sense of the floor. During a performance the stage can become a slick. I didn't want to push off and have my foot slip and slide and twist in the opposite direction.

By now "Places, please" was being called, but a part of me would still resist. There was always one more thing I wanted to do. Making a last-minute check of the stage, I'd remove the towel and the robe, but not my leg warmers. I'd wear them til about twenty seconds to curtain. By then I'd be in my place onstage behind the tent waiting to make my entrance. I tried to get the time I stood behind the tent down to a matter of seconds. But in those remaining seconds I'd eliminate everything but the performance from my mind. I'd be scheming, calculating, preparing all day for this moment, and now I'd narrow my concentration into a simple straight line focused solely on my physicality. I'd feel very alone and revel in the solitude. It wasn't a meditative or spiritual moment; it was just that I could stand there and, no matter who was around me, feel calm. I'd wait for the curtain to rise and the music to start, and I'd burst out onstage. Sometimes I had to go into overdrive and call on an extra reserve of energy to propel the performance because I was fatigued mentally and physically, or because I'd be dancing through a sprained ankle, a bruised toe, an intense backache, a stiff neck, or an inflamed elbow. But usually I had energy to spare now no matter how tired I was.

I love leaping into the air while simultaneously exerting the most precise control possible over my body. Onstage I get an exhilarating sense of abandon and freedom when I move. The sensation of piercing the air, of the air passing my ears as I jump, always thrills me. And I love the fact that the audience is watching me. Stepping out onstage, I would feel more alive than I had during the entire day. This is how it was.

When I hit the stage as the Prodigal, the character is alive inside me. My enthusiasm bursts forth without restraint. But I have to make the character circumspect. The Prodigal is from a noble family. Balanchine adapted the story of Prodigal Son from the New Testament. He described the tale in his book Complete Stories of the Great Ballets. "A son said to his father, Father, give me my portion of goods that has fallen to me. He gathered all together, and took his journey into a far country, and there he wasted his substance with riotous living." The Prodigal has two servants. I must retain a sense of his position, which is revealed in the way I present my body. My gestures are economical, my demeanor calm and reserved until my sisters, who are attempting to stand in the way of my adventure, arrive. Each puts up a little bit of opposition and I become agitated.

The first movement that I do in the variation is to slam my fist into my thigh. In the early years, I'd get bruises the size of half-dollars on my left thigh because I didn't know how to project the moment convincingly. I had to cover these bruises with an extra layer of makeup. Later I learned how to project that moment in a more stylized manner.

After the Prodigal pounds his thigh, he throws up his hands, and the gesture must radiate tension. I never fake this-I know how to produce tension. But I must release it for the next step, the celebrated jump.

The jump is followed by turns, and the most difficult moment of the scene. This is when I come out of the turns, run to the tent, and stop on the very last note of music without moving a muscle. If I lose the beat in this passage, the opening section is ruined, for this is the Father's entrance. The moment is crucial.

In the action, I play off the Father, whose movements are stylized to suggest a sort of Moses or Abraham character. I look to my servants and then over at the gate and perform the act I'd been preparing for—I leave home. I repeat the variation, with great intensity. I leap over the fence, and in a last scream of defiance, I fall into the wings.

As I catch my breath, my chest heaving from the variation, I head for the rosin box, rub my feet in it, and feel the friction that I'm going to need. I cross over to the other wing to make my next entrance. Makeup and costume adjustments are made, and I grab a Kleenex and pat the sweat off because perspiration can cool the muscles as well as make arms and legs slippery for the dancers who have to grab me onstage. I look for the Siren in the wing, and we nod, just to make contact.

I enter downstage left for the second scene. Getting ready, I position myself just outside the edge of the proscenium arch so I can get on quickly. As the time approaches, I politely ask people who are watching from the wings to move aside. Their response makes me uncomfortable. They become intimidated, as if they are actually dealing with the Prodigal Son, and they move away quickly, apologizing, as if they are intruding on a sacred moment. The fact is I just want them to move out of the way so I can get onstage.

As I enter, the drinking companions are clustered downstage right. I look around —it takes a few moments for me to become aware of them. I feel their eyes on my back at first and play off that. I slowly walk over to them, and one by one they offer their hands and I reach out. But almost cruelly, they pull their hands away. Sometimes the boys are off the music and the offering of the hands is rather chaotic, but I work with that and use it in the performance. It's a rare performance when all those hands come out exactly in time to the music. This ballet is not a favorite among young corps de ballet boys. They're covered in ugly headpieces and unflattering costumes, and their gestures are goonlike and grotesque. I understand the lapses in their concentration. When I'm being touched by the goons, I imagine green slime is pouring over me, that eels are slithering across my skin, and the image chills my bones.

I command my servants to offer the goons wine. They swarm around me. I give them wine and some of my other worldly goods to keep them from pawing me. I'm drawn into their activities and I begin to take on their character and form.

My body lowers itself, my head goes forward and my shoulders rise up. The sense of nobility I projected is gone: I'm subsumed into the slime. I jump over the table, thinking of myself as the leader of the revelers, when I'm suddenly aware that the Siren has appeared.

The Prodigal is the center of the drinking companions attention until the Siren arrives. My first reaction is annoyance that the drinking companions are distracted. They're no longer giving me the attention I feel they owe me. But once I take in the sight of the Siren, it's as if a bright light has been shoved in my face, and I flinch. I want to protect my eyes. Then I hold back from the sight, but I'm powerfully drawn to it. I can't resist this overwhelming monument to sensuality. It's my awakening. The Siren's legs are long and voluptuous. Her red cape streams from her, and she is wearing a kind of headdress that seems like an extension of her body. The Siren is a strong, controlling woman, a force. Her movements are cool, frighten-ing. First she spreads her legs. Then she does a backbend and walks on her hands and her pointes. I leer at her legs and am consumed with the thought of touching her limbs, caressing them. Now my glance moves all over her body to her waist, her breasts, her buttocks. It isn't that I want to kiss her, it's strictly sexual, and at that moment when I feel I can touch her, she covers herself with her cape. I inch forward, pull off the cape, and staring at her, think that I must have her.

The pas de deux is critical to the success of any Prodigal Son performance. It's a rite of passage from innocence to ma-turity, but it almost has the force of a rape. I let the Siren dominate me and I feel a sense of release. At the start her arms go around my neck, and she pulls my head to her breast. I'm lost.

I danced the Prodigal opposite many different women, perhaps more than a dozen. Each one had a distinctive style, temperament, and sense of musicality. Each had a different degree of confidence in my ability to partner her. And of course they were all different sizes, and it was up to me to accommodate all of them. Early on I danced the role opposite Gloria Govrin, who has been described as "a magnificently outsized" dancer. Gloria was six foot three inches on pointe, her thighs were bigger than mine, and each of her breasts and my head were roughly the same size. A grand, voluptuous woman, she was well cast as the Siren, but the first time we danced together we had problems. At a crucial point in the pas de deux I hadn't positioned myself correctly with the proper support, and when I put my head through her legs and tried to lift her with my neck during rehearsal, I staggered slightly. Balanchine and half the people watching leapt out of their seats to come to my assistance.

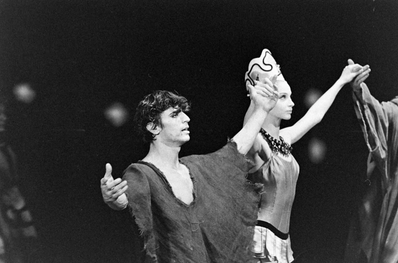

Edward Villella with Karin Von Aroldingen. Photos by Martha Swope, 1970.

Karin von Aroldingen was stately and sensual. Suzanne Farrell was somewhat girlish, petulant, a bit vulnerable as the Siren. Jillana, on the other hand, was wonderfully feminine. Her line was one of the most exquisite in all of classical ballet and was shown off beautifully in the role. Of all the women, Diana Adams, however, left the strongest impression on me. She was passionate, yet utterly ice-cold: she froze my blood.

Diana, of course, had worked extensively on the role with Balanchine. She was a very intelligent dancer and she was especially well-suited for the part. I had made my debut in the ballet with her, and I felt she had guided me through the part, teaching me about it from her own experience. In later years, I was often in her position, the experienced performer leading newcomers through the intricacies of this extraordinary pas de deux.

The trickiest moment in the duet comes when the Siren gets into second position on pointe and, straddling the Prodigal, who is sitting on the floor, sits on his head. Once she's there, there isn't much I can do to help. She has to shift her weight from two legs and her buttocks to one leg and her buttocks. Sitting on my head, she's still on pointe, she's totally unsupported. It's a precarious moment, and each ballerina deals with it differently. If the Siren panics or loses her balance, I have to anticipate it and be fast— and flexible enough—to handle it. Somehow I always manage to avert disaster.

The next moment in the pas de deux the Siren, still on the Prodigal's head, cups her feet over his knees or his shins and rises up to a standing position as he lowers his legs to the floor. The moment the shank of her ballet slipper touches my leg, I grasp the foot and hold it fast, and this gives the Siren a sense of control. I repeat the process with the other foot, but the hair-raising moment comes when the ballerina has to rise up to her full height balancing on my legs while I straighten them and bring them down to the floor, supporting her only with two hands. It's here that Balanchine would say in rehearsal, "Like an elevator." The ballerina has to have confidence in my ability to counter her balance: if either one of us moves too far for-ward, we can both roll over onto the floor in a heap.

Villella with Suzanne Farrell (left) Photo by Martha Swope. (center & right) Photos by Bill Eppridge.

There are other parts of the pas de deux that require the utmost dexterity. At one instance the Prodigal approaches the Siren and, ducking, places his head between her legs and lifts her into the air. I always think of this moment as a unique instance of foreplay. Without changing the position of her arms, the Siren crosses her legs and sits calmly on the Prodigals neck. It's the moment when Balanchine would often tell the ballerina, "Relax, smoke a Kool."

At another point I take hold of the Siren, swing her in the air, wrap her around my waist like a belt, and hold her there. The Siren then slides down to the floor, and I control her descent by bringing my feet and thighs together; I'm partnering her with my legs. Once she's at my feet on the floor, I lift her to her knees, and sliding my feet underneath them, I walk her while her knees are pressing into my feet.

Villell and Farrell. Color photos by Martha Swope, B&W by Bill Eppridge

The pas de deux ends with the Siren and the Prodigal sitting on the floor entwined in an embrace. One of the Siren's arms is wrapped around the Prodigal, but the other is raised behind her head, her fingers fanning out above her headpiece and radiating like a halo, another reference in the choreography to images from Russian icons.

The momentum of the ballet slows down somewhat during the pas de deux, and performing it, I often experienced the most uncanny phenomenon: I was able to monitor the performance from a point of view outside myself, from somewhere in the upper reaches of the theater. A dancer works in front of a mirror taking class and rehearsing, seeing his image come back at him for much of his life, and I think this sense of monitoring the performance can be explained as a consequence of my having looked at my image in the mirror so continually during my career. The phenomenon helped me anticipate mishaps that could occur during the performance so I could avoid them or integrate them into the action.

The pas de deux is followed by another intensely physical scene. In this sequence I am set on by the drinking companions, who tear me off the Siren, turn me upside down, and throw me from one end of the stage to the other. I charge at the boys and try to run through them. They have to stop me and then propel me from one side of the stage to the other. Sometimes a few of them panic. There are times they become a little more physical than necessary, times I find myself crashing onto the floor from ten feet in the air.

At the end of this sequence, I jump up on the table and run along its length to escape the Siren. But the drinking companions block my path by lifting the table at one end on a steep incline so that I can't climb any farther, and I slide down it on my back. At one performance, a shooting pain nearly took my breath away as I slid off the table. After the performance, the pain in my back was worse, but I still couldn't tell what was wrong. The pain persisted for days until one night in my dressing room I was bare-chested and someone said to me, "My god, you've got a splinter in your back the size of a nail." The scene in which the boys attack the Prodigal ends with him stripped of all his worldly goods, nearly naked. Left for dead, the Prodigal slowly regains consciousness and comes out of his stupor. In his nakedness and his abject pose, he resembles the figure of Christ. Drained of all his strength, he's aware of what's happening to him and is filled with the most overwhelming despair. He sinks very, very slowly to the ground. Balanchine once told me, "You have to move in this scene as if you are not moving. You have to make it seem like you are disappearing."

I think of sinking, drowning. The challenge here is to sustain the level of physical intensity I achieved at the beginning of the ballet, but to do so without the benefit of steps. I desperately turn my face up as if the water level is getting higher and higher around me, and this contributes to a theatrical effect because my eyes catch the overhead key light. Collapsing to the floor, I remain completely inert. But after a few beats of music, I set my fingers twitching. I reach out blindly, holding on with one outstretched hand to the upended table. The table is the pillar against which I have been savagely attacked. It supports me and helps revive me. (The table is a fantastic prop that goes from being a picket fence to being a table, a pillar, a crucifix, and the bow of a sailing vessel. In the final scene it's a picket fence again.)

In my wretched and remorseful state, I plead with God to restore my strength, and the depravity into which I have sunk becomes real to me. The Prodigal Son falls three times in the scene as Christ did on the road to Calvary, but I don't know if Balanchine was making a conscious reference to that or, for that matter, if Prokofiev was. (When I questioned Mr. B, however, he said, "The falls are in the music.") As the scene progresses, crawl along and mime the gesture of finding water and drinking it with my hands. It's helpful in a way that I'm parched and thirsty, for it adds to the realism of the moment, but I'm always careful not to carry this too far. I get myself into a fetal position and crawl off into the wings. I try to avoid the patches of sweat on the floor as I crawl because the squeaks can make the scene look hokey.

I spend a brief interlude in the wings, standing on a big sheet that is spread out on the floor. The trunks I'm wearing are removed, and I get into another pair. Misha Arshansky works furiously, streaking slashes of grease over my body with water to depict my begrimed and bedraggled state, his fingers and elbows poking me in the eyes and ribs. And Duckie Copeland and his assistant also hover over me, waiting desperately for a moment to tie my leggings and throw a sackcloth on my back. I grab the staff as all these people are still tugging, pull-ing, and tearing at me, and as the bars of the music for my entrance sound, I lower myself onto my knees and crawl out for the final scene.

The Prodigal, near death, crawls on with the aid of his staff, blindly in search of his homeland. By now I'm really exhausted, and sometimes it's difficult to differentiate between what I'm supposed to be experiencing as the Prodigal and what I'm feeling myself.

In this scene I'm discovered by my sisters nearly unconscious outside the fence. The girls come out and gently lift me up and drag me through the gate. The scene has a particular beauty and poignancy, with a sister on either side of the Prodigal framing him as in an Italian Renaissance painting.

The most moving moment in the ballet for me comes when the Prodigal touches his home ground for the first time; it's almost as if he's being swallowed by it. The Father enters from the house. I see him and make a supplicating gesture. I strive to communicate the terror of the moment for the Prodigal, for even in his daze he's afraid that his father will reject him.

A sweet, intensely lyrical passage sounds in the score as the Father slowly offers his hand to his repentant son. The Son is on his knees now, unsupported by the staff. Placing his arms behind his back, and bowing his head, he walks on his knees to his father. The crawl is difficult to perform because I am hunched over. I get within the reach of the Father, then collapse with my body going forward and my hands up behind my head, a gesture inspired by a Rodin sculpture. I need to calculate this fall because I don't want to land flat on my face at his feet.

But if I land too far away from him, I'm not able to grab his shoes and his legs. And I have to be careful gripping them. On my knees, I reach up to his shoulders and I haul myself up. I put my arm over his shoulder as he covers me with his cloak. He cradles me, and the curtain falls.

Shaun O'Brien (who usually plays the Father) gently lowers me to the ground. I can hear the applause from the other side of the curtain. The performance has taken its toll on my body: my knees are skinned, my insteps are bleeding, my elbows are bruised, there are welts on my arms, and my back hurts like hell. Usually my toes are bleeding, and dirt from the stage clogs my nose and mouth. I'm covered with grime from head to toe. I'm gasping for air. I have just enough energy for the bow.

Onstage there's a commotion, people rushing on and off from the wings as the cast takes places for the curtain call. We organize ourselves in a line for the call, and the Siren and I thank each other. The curtain goes up. It's always a wonderful feeling to be engulfed by the warmth of the audience, and thrilling to come forward for a solo bow. The curtain comes down and I am presented in front of it.

Stepping back inside, I wander around for a minute or two in the midst of the general hubbub. The stage is being swept for the next ballet, and dancers are arriving and warming up. My energy is high but unfocused. I receive a few compliments. The conductor's backstage now and I thank him for the tempi. I have an eye out for Balanchine. He and Stanley are the ones I want to please most. I see Mr. B but wait for him to walk over to me.

I know from experience that Balanchine seldom articulates his feelings about a performance. We all yearn for him to talk to us, and it's a rare occasion when he does. Some dancers linger in the wings trying to catch his eye, but it's futile. It's hard to accept, but this is how Balanchine deals with us. If he says anything at all, it's usually about the music-the tempi were too slow or fast, the orchestra sounded good. He might make a technical comment about a gesture or a step in the pas de deux, and that's all that's necessary. Whatever he says is satisfying. The connection is made, I can return to my dressing room.

Despite the nearly universal regard for the piece, Balanchine remained indifferent to Prodigal Son. I think he was tired of it, bored by it. Some years after I had made my debut in the role, the director of the National Ballet in Washington, D.C., was eager to stage a production of Prodigal that I would dance, but he was uneasy about getting Balanchine's permission. He asked me if I would approach Mr. B for him, so I did.

"Oh, no, dear," Balanchine said to me. "Awful ballet, lousy, rotten. No good. I hate it. Old-fashioned. Terrible bal-let. Don't do it. Do something else."

But I pleaded with him. I said, "It'll be wonderful, Mr. B.

They really want it, and I would really like to do it with them." I made my case for over twenty minutes.

Finally, he sighed and looked at me kindly.

"Okay, dear. You know, ballet is like old coat between old friends. I lend you old coat."

Comments